There's a Demon at the End of this Blog Post

In preparing this site, I revisited several favorite entries on David Bordwell's blog, including This is Your Brain on Movies (Maybe). Go ahead and check it out. DB is talking about what happens when people watch a suspenseful movie. You sit down with Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, and see Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman uncovering secrets in a wine cellar. Upstairs, where Nazi spies are throwing a party, the champagne is running out. You tense up. You feel nervous. They’re going to get caught!

If you’re seeing it for the first time, this is all understandable. Bordwell is more interested in the case where you see Notorious again, and have the exact same response. You already know Grant and Bergman won’t be discovered. So why is your heart racing? Another interesting example is the case of United 93, where Bordwell felt suspense, even though the events it portrays are a forgone conclusion. He looks at several possible explanations, and cites Hitchcock’s adage about giving the audience more information than the characters on screen.

Bordwell’s argues that the emotion “suspense” is triggered involuntarily by the movie cueing you, through editing, music, staging, shot selection, etc., that something bad is about to happen. It works no matter how many times you’ve seen the movie, and if you already know how it turns out. In fact, knowing the outcome is undesirable can make the sensation even more palpable (United 93).

I’ve never been a huge fan of gory slasher movies (they’re not scary), but I do appreciate suspense. Perhaps this is why Hitch and I get along so well. When I read this essay, I took away a very practical lesson: To create suspense, tell the audience something bad is going to happen, and then make them wait for it. I’ve never seen United 93, but I had a similar reaction to watching a video about the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. The shuttle exploded 1 minute and 13 seconds after lift off, and in rewatching the launch, those 73 seconds were excruciating.

I applied this idea to the next film I made, Dirty Hands: We introduce an escaped criminal, Nancy King, having broken into a house, and hear news reports about how dangerous she is. Cue Vince Lang, a lawyer, arriving home, and walking into what we know is a trap. The moment where Nancy attacks him always gets one of the best reactions from the audience.

You might be reading this and thinking, Well, duh! Saying something bad is going to happen makes me expect it- and dread it. But most explicitly scary movies do not even attempt to create suspense. In fact, rather than telling the audience what is about to happen, information is obscured so it’s a bigger surprise when the monster jumps out from the shadows. Yes, I will jump at sudden movements and loud noises, but after a little bit I relax and start wondering if the filmmakers know any other tricks. By the end, I’m rarely impressed.

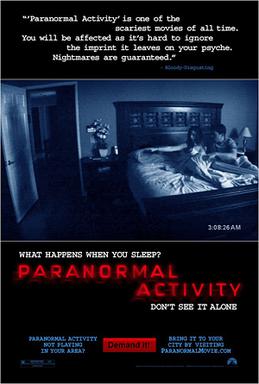

Shortly after reading DB’s essay, I saw the film Paranormal Activity with some friends under the best possible conditions: it was a full house, and everyone was enjoying themselves. The story follows a young couple being haunted by a demon (See? Told you), whose mischief starts out harmless and escalates. The demon only comes out at night, and those scenes are shown in the same static shot of the couple sleeping in bed. After a long stretch of spooky stillness- a light turns on in the hallway. The door creaks open.

Shortly after reading DB’s essay, I saw the film Paranormal Activity with some friends under the best possible conditions: it was a full house, and everyone was enjoying themselves. The story follows a young couple being haunted by a demon (See? Told you), whose mischief starts out harmless and escalates. The demon only comes out at night, and those scenes are shown in the same static shot of the couple sleeping in bed. After a long stretch of spooky stillness- a light turns on in the hallway. The door creaks open.

As far as effects go, these are the oldest ones in the book. Yet no matter how many times we’d seen nothing more than the door move, that shot of the bedroom still meant, Something scary is about to happen. The audience couldn’t help but tense up. I distinctly remember a moment towards the end of the film, when the scene changed to the shot of the couple in bed. A woman behind me, with no further prompting, suddenly screamed. I smiled. DB was right!