To Have Your Cake And Measure Its Momentum Too

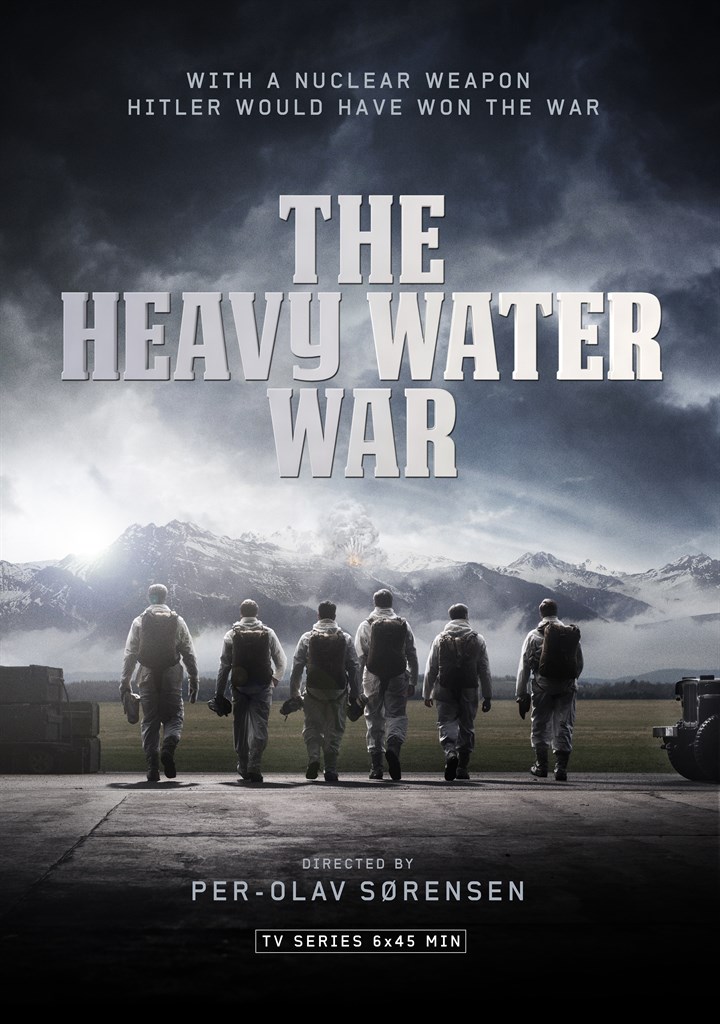

If you can’t get enough Norwegian political/espionage thrillers like Occupied, don’t worry; I have another one for you. The Heavy Water War is also available to stream from Netflix, and covers a British and Norwegian program to sabotage the German atomic bomb project during World War II.

The more I think about it, seeing these two shows together is an interesting juxtaposition. It’s perhaps disheartening that both my forays into Norwegian media involve this once proud nation being overrun by a foreign power. Oh well. Besides this, both shows give us a cross-section of characters- government and military officials making Tough Decisions, soldiers and bureaucrats doing the Dirty Work, and ordinary civilians whose lives are upended by these Uncertain Times.

I thought Occupied had its web of characters intersecting too neatly. I would have liked to see someone like Bente, who owns a restaurant popular with the Russians, not have a major connection to the other power players in the story. Their decisions would still affect her, despite her narrative isolation. This would be the case of many Norwegian civilians who don't have the ear of the Prime Minister.

The Heavy Water War doesn’t try to interweave its characters in the same way, and so doesn’t fall into the same trap. The first few episodes introduce us to Werner Heisenberg, a brilliant physicist[ref]You may have heard of his Uncertainty Principle- a particle's position and momentum cannot be known simultaneously.[/ref], and is our gateway into  understanding why heavy water[ref]The nucleus of a hydrogen atom consists of just a proton. Heavy water is made from deuterium; a hydrogen isotope with a proton and a neutron in its nucleus.[/ref] is so important.[ref]It can be used to help create a sustaining reaction in a nuclear reactor. Heisenberg’s program tried to study these reactions and adapt them into an atomic bomb.[/ref] Afterwards, we meet Erik Henriksen, who runs the Norsk Hydro plant where the heavy water is produced, and his wife Ellen, who gives us a look at how Norwegian civilians are faring under German occupation.[ref]Wikipedia tells me they are fictional.[/ref] We also meet Norwegian soldiers operating in exile from Great Britain.

understanding why heavy water[ref]The nucleus of a hydrogen atom consists of just a proton. Heavy water is made from deuterium; a hydrogen isotope with a proton and a neutron in its nucleus.[/ref] is so important.[ref]It can be used to help create a sustaining reaction in a nuclear reactor. Heisenberg’s program tried to study these reactions and adapt them into an atomic bomb.[/ref] Afterwards, we meet Erik Henriksen, who runs the Norsk Hydro plant where the heavy water is produced, and his wife Ellen, who gives us a look at how Norwegian civilians are faring under German occupation.[ref]Wikipedia tells me they are fictional.[/ref] We also meet Norwegian soldiers operating in exile from Great Britain.

Heisenberg doesn’t play as great a role in the later episodes as he does in the beginning-[ref]I was amused to see Heisenberg’s fabled meeting with his former teacher, Niels Bohr, in Copenhagen in 1940 included in Heavy Water. The story goes that Heisenberg asked to talk to Bohr about something important, and Bohr, fearing his house had been bugged, suggested they walk through the garden. The exact nature of their conversation is unknown, but afterward, the two men never spoke to each other again. Accounts differ, but it’s been speculated that Heisenberg was asking Bohr for help with the German bomb project, and Bohr, not least because he was Jewish, refused. Michael Frayn wrote a play about this cryptic conversation, called Copenhagen.[/ref] by the end, our focus has switched to Leif Tronstad, commanding the sabotage missions in the U.K. The upside of doing this is that Heavy Water has a much more expansive scope than Occupied. That said, this wider view comes at a price: by making each character more disconnected to the others, they’re less developed overall.

As much as Bente’s restaurant feels contrived, she is much more fleshed out than many of Tronstad’s commandos, who perform the daring feats we all came for. This is useful to keep in mind as a writer- the less connected my characters are, the less time I can spend with each of them. The more connected they are, the more I risk coincidences that are beyond belief.

This isn't a dig against The Heavy Water War- it’s well done, and the sabotage raid sequence alone is masterful. One way of doing things isn’t better than the other, they have different purposes. Heavy Water has a more complicated plot, and can afford the narrative risk that comes from characters going off in separate directions. Occupied works because its characters are all intertwined together.

Werner Heisenberg would be the first to tell you, “You can’t have it both ways. It's impossible to observe your characters and measure the plot, too.”